What you might not have taken away from the ensuing media storm is that "The Half Has Never Been Told" is quite a gripping read. Baptist weaves deftly between analysis of economic data and narrative prose to paint a picture of American slavery that is pretty different from what you may have learned in high school Social Studies class.

The whole thing is well worth reading in full. Baptist positions his book in opposition to textbooks that present slavery like a distant aberration of American history, cramming 250 years into a few chapters in a way "that cuts the beating heart out of the story." To counter that image of history, Baptist devotes much of the book to depicting the lived experience of enslavement in a way that's vivid and immediate.

But for those of you who are strapped for time, or who want a peek into the book before committing to the full 420 pages, here are five of his key arguments:

1) Slavery was a key driver of the formation of American wealth.

Baptist argues that our narrative of slavery generally goes something like this: it was a terrible thing, but it was an anomoly, a sort of feudal throwback within capitalism whose demise would inevitably come with the rise of wage labor. In fact, he argues, it was at the heart of the development of American capitalism.

Baptist crunches economic data to come up with a "back-of-the-envelope" estimate of how much slavery contributed to the American economy both directly and indirectly. "All told, more than $600 million, or almost half of the economic activity in the United States in 1836, derived directly or indirectly from cotton produced by the million-odd slaves -- 6 percent of the total US population -- who in that year toiled in labor camps on slavery's frontier."

By 1850, he writes, American slaves were worth $1.3 billion, one-fifth of the nation's wealth.

2) In its heyday, slavery was more efficient than free labor, contrary to the arguments made by some northerners at the time.

Drawing on cotton production data and firsthand accounts of slaveowners and the formerly enslaved, Baptist finds that ever-increasing cotton picking quotas, enforced by brutal whippings, led slaves to reach picking speeds that stretched the limits of physical possibility. "A study of planter account books that record daily picking totals for individual enslaved people on labor camps across the South found a growth in daily picking totals of 2.1 percent per year," Baptist writes. "The increase was even higher if one looks at the growth in the newer southwestern areas in 1860, where the efficiency of picking grew by 2.6 percent per year from 1811 to 1860, for a total productivity increase of 361 percent."

Free wage laborers were comparatively much slower. "Many enslaved cotton pickers in the late 1850s had peaked at well over 200 pounds per day," Baptist notes. "In the 1930s, after a half-century of massive scientific experimentation, all to make the cotton boll more pickable, the great-grandchildren of the enslaved often picked only 100 to 120 pounds per day."

3) Slavery didn't just enrich the South, but also drove the industrial boom in the North.

The steady stream of large quantities of cotton was the lifeblood of textile mills in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and generated wealth for the owners of those mills. By 1832, "Lowell consumed 100,000 days of enslaved people's labor every year," Baptist writes. "And as enslaved hands made pounds of cotton more efficiently than free ones, dropping the inflation-adjusted price of cotton delivered to the US and British textile mills by 60 percent between 1790 and 1860, the whipping-machine was freeing up millions of dollars for the Boston Associates."

Slavery in the South was also instrumental in changing the demographic face of the North, as Europeans streamed in to work in the region's factories. "Outside of the cotton ports, jobs were scarce for immigrants in the slave states during the 1840s, and they had no desire to compete with workers driven by the whipping-machine," Baptist explains. "The immigrants' choice to move to the North had significant demographic impact, raising the northern population from 7.1 million in 1830 to 10 million in 1840, and then to over 14 million by 1850. In the same period, the South grew much more slowly, from 5.7 million in 1830 to almost 9 million."

4) Slavery wasn't showing any signs of slowing down economically by the time the Civil War came around.

Here's Baptist:

In the 1850s, southern production of cotton doubled from 2 million to 4 million bales, with no sign of either slowing down or quenching the industrial West's thirst for raw materials. The world's consumption of cotton grew from 1.5 billion to 2.5 billion pounds, and at the end of the decade the hands of US fields were still picking two-thirds of all of it, and almost all of that which went to Western Europe's factories. By 1860, the eight wealthiest states in the United States, ranked by wealth per white person, were South Carolina, Mississippi, Louisiana, Georgia, Connecticut, Alabama, Florida, and Texas -- seven states created by cotton's march west and south, plus one that, as the most industrialized state in the Union, profited disproportionately from the gearing of northern factory equipment to the southwestern whipping machine.And it provided the basis for the creation of sophisticated financial products: slave-backed bonds that Baptist says were "remarkably similar to the securitized bonds, backed by mortgages on US homes, that attracted investors from around the globe to US financial markets from the 1980s until the economic collapse of 2008."

Slave-backed bonds "generated revenue for investors from enslavers' repayments of mortgages on enslaved people," Baptist writes. "This meant that investors around the world would share in revenues made by hands in the field. Thus, in effect, even as Britain was liberating the slaves of its empire, a British bank could now sell an investor a completely commodified slave: not a particular individual who could die or run away, but a bond that was the right to a one-slave-sized slice of a pie made from the income of thousands of slaves."

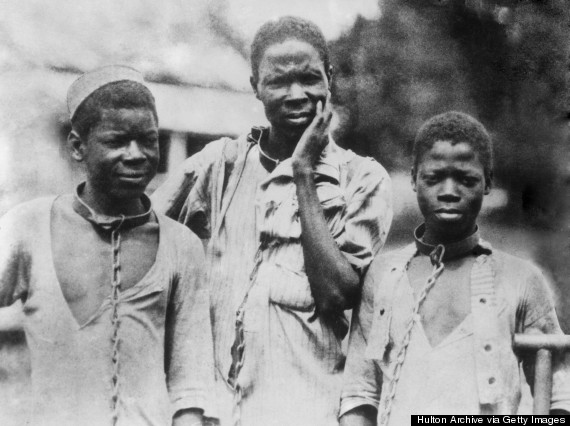

A formerly enslaved woman, photographed on a farm near Greensboro, Alabama in 1941.

5) The South seceded to guarantee the expansion of slavery.

There are many competing explanations for what moved the South to secede. Baptist argues that the main driving reason was an economic one: slavery had to keep expanding to remain profitable, and Southern politicians wanted to ensure that new western states would be slave-owning ones. "Ever since the end of the Civil War, Confederate apologists have put out the lie that the southern states seceded and southerners fought to defend an abstract constitutional principle of 'state's rights.' That falsehood attempts to sanitize the past," Baptist writes. At every Democratic party national convention, "participants made it explicit: they were seceding because they thought secession would protect the future of slavery."

So why is it important to revisit this history now, nearly 150 years after slavery ended?

Baptist comes at the topic from the standpoint that our understanding -- or misunderstanding -- of slavery has policy implications for the present. (In that way, the book is complementary reading to Ta-Nehisi Coates' much talked-about Case For Reparations). "If slavery was outside of US history, for instance -- if indeed it was a drag and not a rocket booster to American economic growth -- then slavery was not implicated in US growth, success, power and wealth," Baptist writes. "Therefore none of the massive quantities of wealth and treasure piled by that economic growth is owed to African Americans." Anyone who believes that, his book aims to show, really hasn't heard the half of it. Slavery was a key driver of the formation of American wealth.

Baptist argues that our narrative of slavery generally goes something like this: it was a terrible thing, but it was an anomoly, a sort of feudal throwback within capitalism whose demise would inevitably come with the rise of wage labor. In fact, he argues, it was at the heart of the development of American capitalism.

Baptist crunches economic data to come up with a "back-of-the-envelope" estimate of how much slavery contributed to the American economy both directly and indirectly. "All told, more than $600 million, or almost half of the economic activity in the United States in 1836, derived directly or indirectly from cotton produced by the million-odd slaves -- 6 percent of the total US population -- who in that year toiled in labor camps on slavery's frontier."

By 1850, he writes, American slaves were worth $1.3 billion, one-fifth of the nation's wealth.

2) In its heyday, slavery was more efficient than free labor, contrary to the arguments made by some northerners at the time.

Drawing on cotton production data and firsthand accounts of slaveowners and the formerly enslaved, Baptist finds that ever-increasing cotton picking quotas, enforced by brutal whippings, led slaves to reach picking speeds that stretched the limits of physical possibility. "A study of planter account books that record daily picking totals for individual enslaved people on labor camps across the South found a growth in daily picking totals of 2.1 percent per year," Baptist writes. "The increase was even higher if one looks at the growth in the newer southwestern areas in 1860, where the efficiency of picking grew by 2.6 percent per year from 1811 to 1860, for a total productivity increase of 361 percent."

Free wage laborers were comparatively much slower. "Many enslaved cotton pickers in the late 1850s had peaked at well over 200 pounds per day," Baptist notes. "In the 1930s, after a half-century of massive scientific experimentation, all to make the cotton boll more pickable, the great-grandchildren of the enslaved often picked only 100 to 120 pounds per day."

) Slavery didn't just enrich the South, but also drove the industrial boom in the North.

The steady stream of large quantities of cotton was the lifeblood of textile mills in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and generated wealth for the owners of those mills. By 1832, "Lowell consumed 100,000 days of enslaved people's labor every year," Baptist writes. "And as enslaved hands made pounds of cotton more efficiently than free ones, dropping the inflation-adjusted price of cotton delivered to the US and British textile mills by 60 percent between 1790 and 1860, the whipping-machine was freeing up millions of dollars for the Boston Associates."

Slavery in the South was also instrumental in changing the demographic face of the North, as Europeans streamed in to work in the region's factories. "Outside of the cotton ports, jobs were scarce for immigrants in the slave states during the 1840s, and they had no desire to compete with workers driven by the whipping-machine," Baptist explains. "The immigrants' choice to move to the North had significant demographic impact, raising the northern population from 7.1 million in 1830 to 10 million in 1840, and then to over 14 million by 1850. In the same period, the South grew much more slowly, from 5.7 million in) Slavery didn't just enrich the South, but also drove the industrial boom in the North.

The steady stream of large quantities of cotton was the lifeblood of textile mills in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, and generated wealth for the owners of those mills. By 1832, "Lowell consumed 100,000 days of enslaved people's labor every year," Baptist writes. "And as enslaved hands made pounds of cotton more efficiently than free ones, dropping the inflation-adjusted price of cotton delivered to the US and British textile mills by 60 percent between 1790 and 1860, the whipping-machine was freeing up millions of dollars for the Boston Associates."

Slavery in the South was also instrumental in changing the demographic face of the North, as Europeans streamed in to work in the region's factories. "Outside of the cotton ports, jobs were scarce for immigrants in the slave states during the 1840s, and they had no desire to compete with workers driven by the whipping-machine," Baptist explains. "The immigrants' choice to move to the North had significant demographic impact, raising the northern population from 7.1 million in 1830 to 10 million in 1840, and then to over 14 million by 1850. In the same period, the South grew much more slowly, from 5.7 million in 1830 to almost 9 million."

4) Slavery wasn't showing any signs of slowing down economically by the time the Civil War came around.

Here's Baptist:

In the 1850s, southern production of cotton doubled from 2 million to 4 million bales, with no sign of either slowing down or quenching the industrial West's thirst for raw materials. The world's consumption of cotton grew from 1.5 billion to 2.5 billion pounds, and at the end of the decade the hands of US fields were still picking two-thirds of all of it, and almost all of that which went to Western Europe's factories. By 1860, the eight wealthiest states in the United States, ranked by wealth per white person, were South Carolina, Mississippi, Louisiana, Georgia, Connecticut, Alabama, Florida, and Texas -- seven states created by cotton's march west and south, plus one that, as the most industrialized state in the Union, profited disproportionately from the gearing of northern factory equipment to the southwestern whipping machine.5. ) The South seceded to guarantee the expansion of slavery.

There are many competing explanations for what moved the South to secede. Baptist argues that the main driving reason was an economic one: slavery had to keep expanding to remain profitable, and Southern politicians wanted to ensure that new western states would be slave-owning ones. "Ever since the end of the Civil War, Confederate apologists have put out the lie that the southern states seceded and southerners fought to defend an abstract constitutional principle of 'state's rights.' That falsehood attempts to sanitize the past," Baptist writes. At every Democratic party national convention, "participants made it explicit: they were seceding because they thought secession would protect the future of slavery."

So why is it important to revisit this history now, nearly 150 years after slavery ended?

Baptist comes at the topic from the standpoint that our understanding -- or misunderstanding -- of slavery has policy implications for the present. (In that way, the book is complementary reading to Ta-Nehisi Coates' much talked-about Case For Reparations). "If slavery was outside of US history, for instance -- if indeed it was a drag and not a rocket booster to American economic growth -- then slavery was not implicated in US growth, success, power and wealth," Baptist writes. "Therefore none of the massive quantities of wealth and treasure piled by that economic growth is owed to African Americans." Anyone who believes that, his book aims to show, really hasn't heard the half of it.